The door of Ch’an is entered by Wu. When we meditate on Wu we ask “What is Wu?” On entering Wu, we experience emptiness; we are not aware of existence, either ours or the world’s.

E-MAIL: admin@relaxmid.com

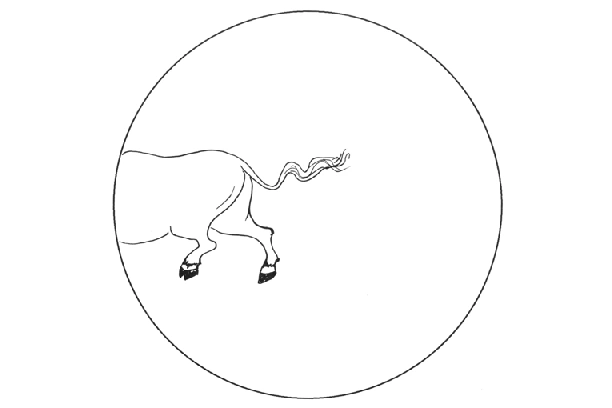

After looking for a long time, the ox herder sees the tail of the ox sticking out from behind a tree. He’s very happy, but the ox is still not in his hands.

This is equivalent to seeing your self-nature for the first time. It is comparable to traveling a long distance and finally spotting a high mountain (your goal) in the distance ─ close enough to see, but too far away to

climb. How high it really is and what is on it is still not clear. Also, you lose sight of the mountain when the skies are cloudy. But at least you have seen the mountain, or in the case of the pictures, the ox. Faith is firmly established.

In Ch’an, this stage is sometimes called “having opened one eye.” But there are many eyes ─ physical eyes, Dharma eyes, wisdom eyes, liberation eyes, and others ─ so you are still nearly blind. With this type of experience, you might also say that your eye opened for a moment, and then closed again.

Imagine walking on a dark night, when it’s raining hard and pitch black. Suddenly, a bolt of lightning flashes and illuminates the area for a brief moment. Before, you wandered and stumbled in the darkness, but now, because of the lightning flash, you are aware of your immediate surroundings. You can walk with certainty, but only for a short distance. Up ahead it’s still dark.

No matter how you describe it, this type of experience is valuable, even it isn’t deep. Are there people who open all their eyes and don’t close them again? Yes, there are. But such people are rare. What is it that I’m talking about?

Student: It sounds like what Zen masters call kensho.

Shih-fu: Is kensho a big deal?

Student: From what I’ve observed, no.

Shih-fu: Is a person who has seen his self-nature a common person, or is he a saintly person or sage?

Student: During the time the eye remains open, which may be a day or a week or a month, he would be a sage. But after it closes, he would be a common person again.

Shih-fu: Actually, the person who has had that experience is the same as a common person. He still has the same vexations. At least now, however, he’ll be more aware of vexations as they arise.

These questions address situations which can be dangerous. For instance, a person who has had this experience may believe that he no longer has any vexations, and that he is truly liberated. When vexations do appear, he’ll then doubt that the experience was really of any value. It’s also possible that, even after vexations reappear, the person may deceive himself and others by acting like a saintly person.

There are three ways for a teacher to help a person like this. One way is to let the person know that although his kensho is good, it is still shallow. It is like a baby bird who knows enough to open its mouth to eat, but who has yet to grow feathers. How can it think of flying at this point?

A person who has a shallow kensho experience and thinks he’s qualified to be a master is endangering himself and others. It must be made clear to the person that he has to continue working hard in his practice. He is still featherless.

The second way for a master to help this person is to remind him of the five main precepts of Buddhism: no killing, no stealing, no sexual misconduct, no false speech (lying, talking behind people’s backs, or falsely claiming you are a master), and not indulging in intoxicants.

A deeply enlightened master need not pay attention to the precepts, because his wisdom and samadhi power are never apart from the precepts. There is no need to add any rules. For the person who has just had a kensho experience, however, the precepts are like the nest which protects the baby bird, and it would be as dangerous for the person to leave the precepts as it would for the bird to leave the nest.

There are practices which seem to contradict this. Have you heard about certain Buddhists groups where monks drink alcohol, calling it “wisdom soup?”

Student: I’ve heard of something like that. The word is upaya. It means that expedient methods, which can include acts of misbehavior, are justifiable if it is done for the good of the student. As I understand it, the idea is to break the narrow conception of the student. One master, for example, would eat hamburgers in front of his students if they became too attached to the idea of not eating meat.

Shih-fu: It is true that great masters can use expedient methods to help students. For example, Ch’an master Nan-ch’uan cut a cat in half as a means of teaching his disciples. But when lesser masters try to imitate great Ch’an masters, it usually leads to problems. I consider myself to be a lesser Ch’an master, so I’m not going to imitate the great ones. In the history of Ch’an and Zen Buddhism, only one great master out of many killed a cat. Generally speaking, Ch’an masters should maintain the precepts. Master Hsu-yun, probably the greatest Ch’an master in recent history, strictly adhered to the precepts.

The third way to deal with a recent kensho experience is to adhere to the outer forms and rituals of the practice. Having definite forms of practice, attire and behavior helps to create a better environment in which to practice. Of course, I’m referring to monks and nuns, but the same holds true for lay practitioners. Maintaining the proper outer form, the proper demeanor, will help a practitioner not to stray from the practice.

Actually, if a person who has had a shallow enlightenment continues to practice hard, adheres to the precepts, and maintains the rituals, then to a certain extent he is in a position to help other people.

I am sorry to say that Chinese practitioners do not keep up this outer form. Today it seems most practitioners are sloppy in their practice. For this reason you don’t see many Chinese Ch’an masters. There are more Japanese Zen masters. In the future, I will try to train students and disciples in this aspect of the practice.

PREVIOUS: The Second Picture | Ox Herding at Morgan’s Bay

NEXT: The Fourth Picture | Ox Herding at Morgan’s Bay