The door of Ch’an is entered by Wu. When we meditate on Wu we ask “What is Wu?” On entering Wu, we experience emptiness; we are not aware of existence, either ours or the world’s.

E-MAIL: admin@relaxmid.com

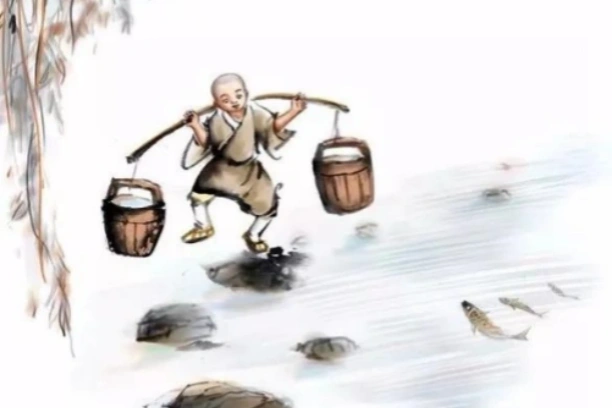

Always acting alone, walking alone,

Together the enlightened travel the Nirvana road.

The tune is ancient, the spirit pure, the style poised,

The face drawn, the bones hardened; people take no notice.

These four lines describe a practitioner’s mind as well as his body. A great practitioner’s lifestyle is extraordinarily independent. Each practitioner leads a solitary life and follows his own path to Nirvana. Though there are innumerable paths, every path is the same. Furthermore, each practitioner must walk his path alone. But although a practitioner is alone, he is not lonely. He does not need company. His companion is the Dharma, and his life is the practice. To enter the realm of no-birth and no-death, you must have this kind of attitude.

Although Ch’an teachings are new in the West, Ch’an itself is ancient. It has existed since beginningless time. Likewise, a great practitioner also seems ancient in his appearance and manner. Outwardly, he may seem thin and impoverished, but when you look more closely, you will see that he is spirited and healthy. You would not think he is a sage because he does not call attention to himself; fame, power and material riches mean nothing to him. His manner is noble and poised, and his mind is silent and peaceful.

During retreat, I always tell people to isolate themselves. It is not an easy thing to do. You all have families and friends that you care for and think about, but you must put your thoughts of them aside when you participate in a retreat. When you have scattered thoughts, they usually involve relations with other people. One student told me that he did not want to be on a retreat if his girlfriend also attended, because he would always be wondering how she was doing. His girlfriend is not here, but I am sure his mind is often with her. The walls of the Ch’an hall cannot stop the mind.

There are several steps to isolating yourself. First, you must isolate yourself from the people around you: as far as you are concerned, you are the only person meditating in this hall. Do not think about the person next to you, no matter if the person coughs, sways, or jumps up to go to the bathroom all the time. None of it has anything to do with you. When you sit, you may hear someone laugh, cry, or even scream. Naturally, it will arouse your curiosity, but you must learn to separate yourself from the people around you.

The next step is to isolate yourself from the realms of sight and sound and light and shadow. It is relatively easy to put down sights and sounds of the external environment. If you cannot separate yourself from honking horns and blaring radios, then your mind is extremely scattered. But you must also isolate yourself from internal disturbances ─ those of the mind and body. No matter what you see, hear, feel or imagine, do not cling to it. This is difficult to do. If you can isolate yourself from these phenomena, then your practice will be smooth and your progress steady.

There is a story of an old lady who supported a monk for twenty years, allowing him to meditate in a hut near her home. One day, she instructed her eighteen-year-old daughter to take food to the monk, hug him, and then ask him what he felt. The daughter did as she was told. When she hugged the monk and asked him how he felt, he said, “Like a dry stick leaning against a cold cliff.”

The daughter reported everything to the old woman. Furious, the woman grabbed a broom and went to the monk’s hut. “Here I’ve supported you for twenty years, thinking you were a real practitioner! Get out!” she yelled as she chased him away with her broom. After he was out of sight, she burned down the hut.

The woman was angry because the monk had only attained the first stage of isolation. He had isolated himself from people and the external environment, but he was attached to his isolation. He had not succeeded in transcending the disturbances within his own mind.

Obviously, it is not easy to advance along the Buddha path. You must first work with the body and environment. If you could immediately isolate yourself from the mind, there would be no need for Ch’an retreats. Once you completely isolate the mind from internal and external phenomena, you must then break apart the isolated mind. The result is enlightenment. However, you should not think about enlightenment. All you have to do is stay on the method and ignore everything else. Refrain from comparing yourself to others. Whether or not they are doing well is not your concern ─ this is good advice for daily life as well as for a retreat. Only with such an attitude will it be possible to enter the door of Ch’an.

Realize that isolating yourself from other people does not mean going into seclusion. It is possible to be in a crowd and still be isolated. Envision yourself as being alone, because in truth, you are alone. You are born into this world alone, and you will die alone. Even if you tie yourself to your lover, take poison together, and die at the same instant, you will still leave the world alone. Your karma is uniquely your own.

Isolating yourself from everyone and everything is a difficult skill to develop. For this reason, serious practitioners are often encouraged by their teachers to practice ─ at least for a while ─ alone and away from society. In ancient China and Tibet, many great practitioners spent long periods of time practicing in seclusion. In modern times as well, many practitioners go on personal retreats. I spent six years practicing alone in the mountains of Taiwan. I would not have ignored people had they approached me, but no one ever visited. I had no telephone, no mail, no company. It was a humbling experience. I felt free, yet somber. In general, it would benefit your practice if people ignored you, or even despised you. If people treat you like a celebrity or hero, then your practice will probably suffer.

In modern China, there was a famous monk named Lai-kuo. When he was still a young man, he became the abbot of a well-known monastery. After three years, he retired, changed his identity, and went to a monastery where no one knew him. He requested the job of cleaning the toilets. He spent several years in uninterrupted practice, until one day a disciple from the old monastery recognized him. Lai-kuo begged him to keep his identity a secret, but word quickly spread that he had once been an abbot.

Before anyone could talk to him, he gathered his clothes and left to find another place, because he felt he needed more time to practice. Eventually, people found him again and dragged him back to the monastery.

If it is not people pulling your body from the practice, it is thoughts pulling your mind from the method. Whether you practice in solitude or in a crowd, you must try to isolate your mind. It may seem foolish to isolate yourself, but it works. In society there are many distractions and attachments. As soon as you generate the slightest craving or aversion for anything, obstructions will appear in your practice.

On this retreat, one of my students told me that his cousin recently died of cancer, and that he felt bad. I asked him, “Who is suffering the most from your cousin’s death?” He said, “Probably his mother.”

I told him, “Then, instead of wasting time mourning, which is really feeling sorry for yourself, you should use your wisdom from the practice to help ease the misery of your aunt. Also, you should use your method to help transfer merit to your dead cousin, so that he may be reborn in a better place. What good is mourning?” Of course, I would not say this to everyone. Those who have a sound grasp of Buddhadharma and a stable foundation of practice, however, would be able to understand this advice and put it into practice.

It is already the end of the third day. Hopefully, you will take advantage of the time remaining on this retreat and learn to isolate yourself. Now, while you have the opportunity, work hard. When you return to daily life, it will be impossible to isolate yourself from family, friends and the environment. Vexations will inevitably arise. However, if your practice is strong, you will be able to cut off these vexations before they become rooted in your mind.

PREVIOUS: Day 2 False Enlightenment: Reaching for the Moon in the Water | The Sword of Wisdom

NEXT: Day 4 The Wealth of Wanting Little | The Sword of Wisdom